Pigs do fly[1]. But only the more privileged ones. Yes, animals that fly are not restricted to those with their own wings. It’s true that the animal kingdom has been showing us how to fly long before powered flight took-off. Nothing more graceful than a bird of pray swooping and diving. We (humans) can’t match much of what they do with our flying machines however hard we try.

Birds long inspired great thinkers. They opened the prospect of human flight. If they can do it – why can’t we? Surely the right combination of aerodynamic structures and a source of power would solve the problem. Shocking, in a way, that it wasn’t until a couple of keen bicycle repair men and a smart mechanic persisted until they had a working machine. That was only just over a hundred years back.

So, today’s novelty News item[2] of a cat that didn’t want to leave an aircraft puts a smile on my morning face. For all the farm cats I have known, the story doesn’t surprise me at all. It’s the sort of situation where humans are almost powerless in the face of the preferences of a feline.

Naturally, the engineering staff of an airline will have a good look at where the cat has been in its wanderings. There’s always the remote chance for a rogue moggy to play with something they shouldn’t ought to play with. Even on a modern Boeing 737.

I used the word “remote” but there are definite cases of loose animals causing air safety hazards. Looking this one up, because it sits vaguely in my memory, I do recall a dog that crewed through electrical cables after it got free in a cargo hold. Now, however lovable and cuddly a dog maybe that’s a place that no one wants to be in.

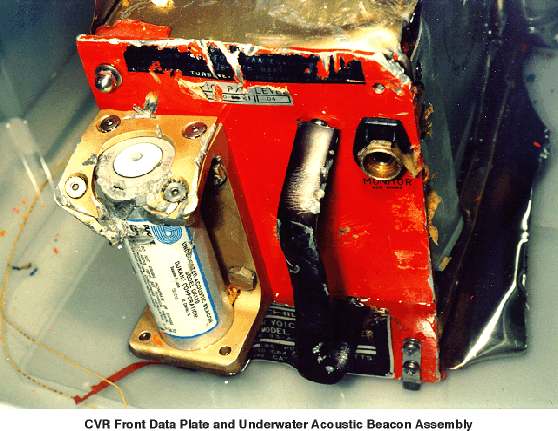

Back in 2002, American Airlines Flight 282 approached New York’s JFK. It was a Boeing 757 that landed with chewed-up electrical cables. Crew members heard noises coming from the cargo hold and found that some aircraft radio and navigational equipment wasn’t working. A dog had chewed its way through a cargo bulkhead and attacked wires in an electronics compartment.

A quick search reveals that there are more cases of incidents caused by loose animals than might first be thought. Animals are potentially hazardous cargo. Sadly, often these flight incidents are not good for the animals concerned.

One thing to remember is that a large aircraft, at flight altitude, is pressurised. That’s not at the air pressure on the ground (unless an airport is a long way up a mountain range). A dog with breathing difficulties is going to find an aircraft environment distressing. Dogs can be skillful escape artists. Myself, I’m not keen to share a flight with them.

[1] https://intradco-global.com/livestock-transport/

[2] https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/33273791/cat-causes-chaos-ryanair-plane-rome/