Hype has its place. Being positive while buffeted by the inevitable ups and downs of life is purposeful and necessary. What’s not true, and might be the impression, is that electric aviation is easy. When forging ahead to build a future, that is not yet realised, there’s a need to maintain confidence. However, being blinded by the light doesn’t help when it comes to tackling difficult problems. Proof-of-concept is just that.

The big positives of electric aviation are the environmental benefits. Electric aviation is spawning many new types of aircraft and the possibilities of new types of operation. So, there’s no doubt that this is an exciting time to be an aviation enthusiast. What a great time to be in aerospace design and manufacturing. Here we are at the start of a new era[1].

My point is that high power electrics, and their control are not “simple” or intrinsically safe in ways other types of aircraft are not. I know that’s a double negative. Better I say that high power electrics, operated in a harsh airborne environment have their own complexities, especially in control and failure management. Fostering an illusion that the time between having an idea and getting it into service can be done in the blink of an eye is dangerous.

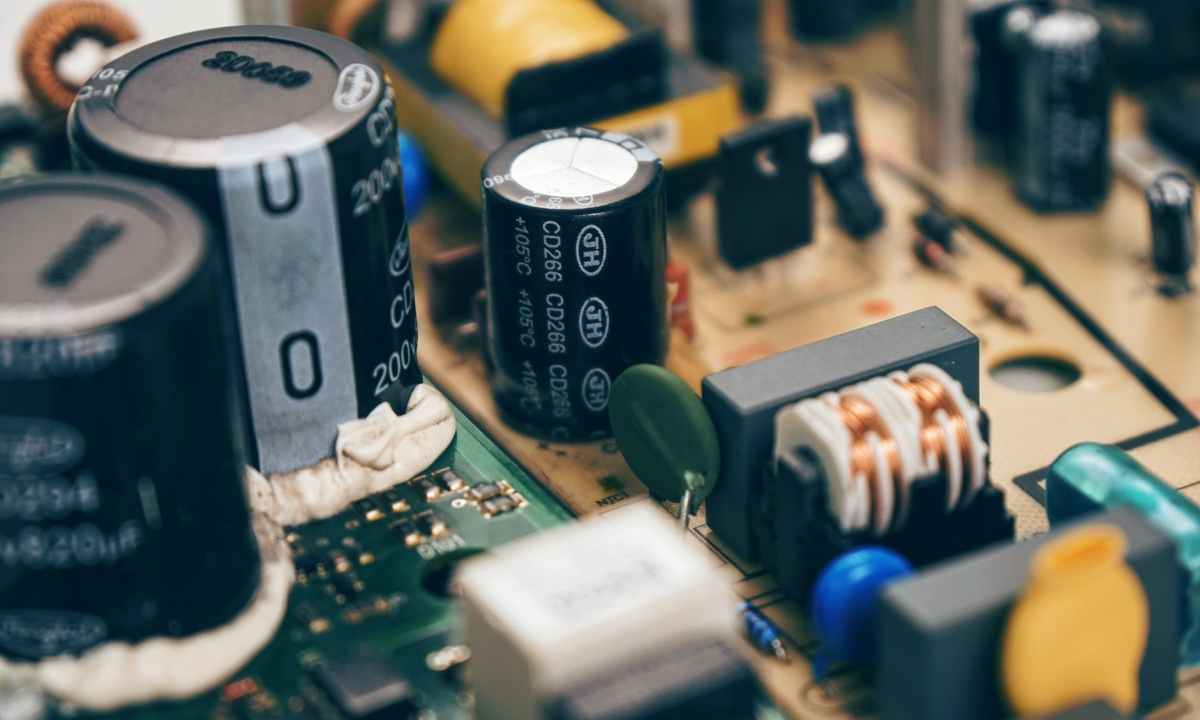

The design, development and production of advanced aircraft power distribution, control and avionics systems is not for the faint hearted. Handling large amounts of electrical power doesn’t have the outward evidence of large spinning mechanical systems but never underestimate the real power involved. Power is power.

The eVTOL aircraft in development deploy innovative design strategies. There’s a lot that’s new. Especially all together in one flying vehicle. Everyone wants fully electric and hybrid-electric aircraft with usable range and payload capacity. So, the race is one. Companies are productising the designs for electric motors of powers of greater than 10kW/kg[2] with high efficiency and impressive reliable. These systems will demand suitable care and attention when they get out into the operating world.

A 500kW motor will go up with one hell of a bang and fire when it fails. The avionics may shut it down, but everything will have to work smoothy as designed every day, not just in-flight but on the ground too. Suppressing an electrical fire isn’t the same as a conventional fuel fire either. To fix these machines the care needed will be great. 1000 Volt connections capable of supplying high power can kill.

Not wishing to be focussed on the problems but here I go. Another major problem is the number of qualified engineers, with knowledge and experience who can work in this area. The companies who know how to do this demanding work are desperately searching for new people to join their ranks.

Educators are starting to consider these demands as they plan for the future. Sadly, there’s not so many of them across the globe who are so foward looking.

The global aviation industry needs to step-up and train people like crazy. The demand for Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) is self-evident. That’s true in design, production, and maintenance. Post COVID budgets maybe stretched but without the big-time investments in people as well as machinery success will be nothing but an illusion.

POST1 : Or 150 kW motors when you have many of them going at once. Rolls-Royce Electrical Testing eVTOL Lift Motor | Aviation Week Network

POST 2: Getting ready Preparing Your Airport for Electric Aircraft and Hydrogen Technologies | The National Academies Press

[1] https://smg-consulting.com/advanced-air-mobility

[2] https://www.electricmotorengineering.com/h3x-new-investments-for-the-sustainable-aviation/