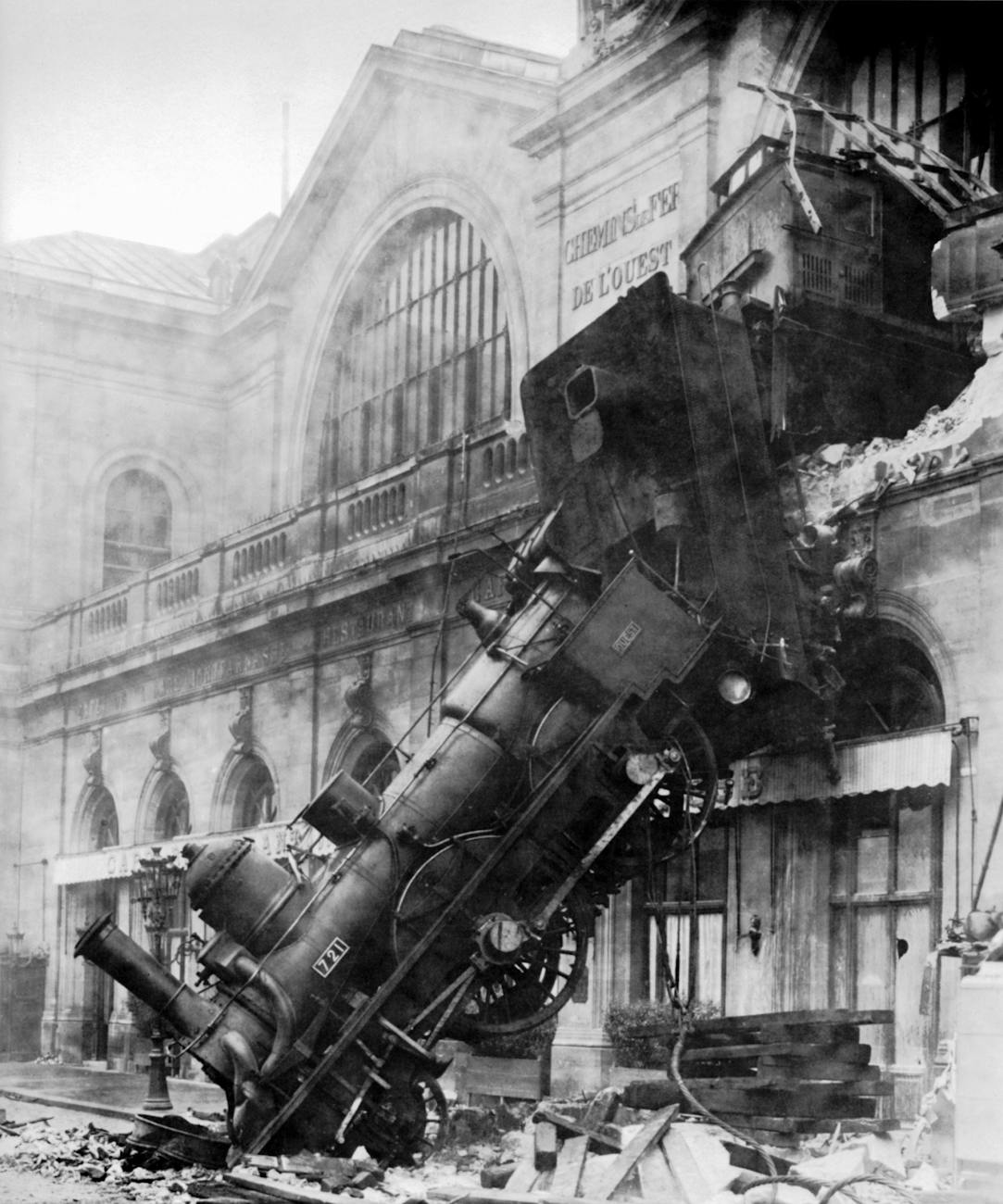

Let me clarify. I can no more predict the future than is illustrated in the humour of this news report. “Psychic’s Gloucester show cancelled due to ‘unforeseen circumstances[1]‘”

Predicting the outcome of an aircraft accident investigation is just as fraught with unforeseen circumstances. For a start, the evidence base is shallow in the first weeks of an investigation. As the clock ticks so increasingly, new information either confuses or clarifies the situation.

Despite the uncertainty, aviation professionals do need to try to anticipate the findings of a formal investigation before they are published or communicated in confidence. It’s not acceptable to sit back and wait to be told what has been found.

In aviation, post-accident there is an elevation of operational risk. The trouble is that assessing that elevation is hindered by the paucity of reliable information. Equally, a proliferation of speculation can escalate risk assessments beyond what is needed. The reverse is true too.

Let’s look at the difference between commentary and speculation. One is based on evidence and the other may not be. One takes the best professional assessment and the other may be more to do with beliefs, prejudices or the latest fashionable thinking.

In reality, it’s not quite as binary. Since speculation in the financial sense may be based on a lot of calculation and risk assessment. Generally, though there is an element of a leap of faith. Opinions based upon past experiences commonly shape thinking.

Commentary on the other hand, like sports commentary is describing what’s happening based upon what’s known. Sometimes that includes one or two – what ifs. In football, that match deciding penalty that was only missed but for a small error.

Commentary includes analysis and study of past accidents and incidents. Trying to pick-up on any apparent trends or patterns is of paramount importance.

Those responsible for aircraft operations, whether they be airlines or safety regulators, need to have an immediate response. That maybe done in private. Their decision-makers need to have a theory or conjecture based on as much analysis and evidence as is available. Like it or not, the proliferation of commentary and speculation does have an impact.

In a past life, one of the actions that my team and I took was to compile a “red book” as quickly as possible post-accident. That document would contain as much reliable information as was available. Facts like aircraft registration details, a type description, people, places and organisation details that were verifiable. This was not a full explanation. It was an analysis, compilation and commentary on what had happened. The idea being that decision-makers had the best possible chance of acting in a consistent manner to reduce risk in the here and now.

[1] https://www.gloucestershirelive.co.uk/whats-on/whats-on-news/psychics-gloucester-show-cancelled-due-7250094