Reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) is making the News in the UK. An unknown number of buildings are deemed dangerous because of the aging of this material[1]. RAAC has a limited lifespan. It’s inferior to standard concrete but lightweight and low-cost at the start of its life. It was typically used in precast panels in walls, roofs and sometimes floors.

The UK Government says it has been aware of RAAC in public sector buildings, including schools, since 1994. Warnings from the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) says that RAAC could – collapse with little or no notice. This “bubbly” form of concrete can creep and deflect over time, and this can be aggravated by water penetration. So, regular inspection and maintenance are vital to keep this material safe. Especially in a country known for its inclement weather.

It’s reasonable to say there lies a problem. The public estate has been through a period of austerity. One of the first tasks to get cut back, when funds are short is regular maintenance. Now, I am making some assumptions in this respect, but they are reasonable. Public sector spending has been under significant pressure for a long time.

The other dogmatic notion that has hindered a solution to this building problem is centralisation. There was a time when local authorities managed schools. They still do but in smaller numbers. Centralised funding has decreased the power of local people to address problems with the school estate.

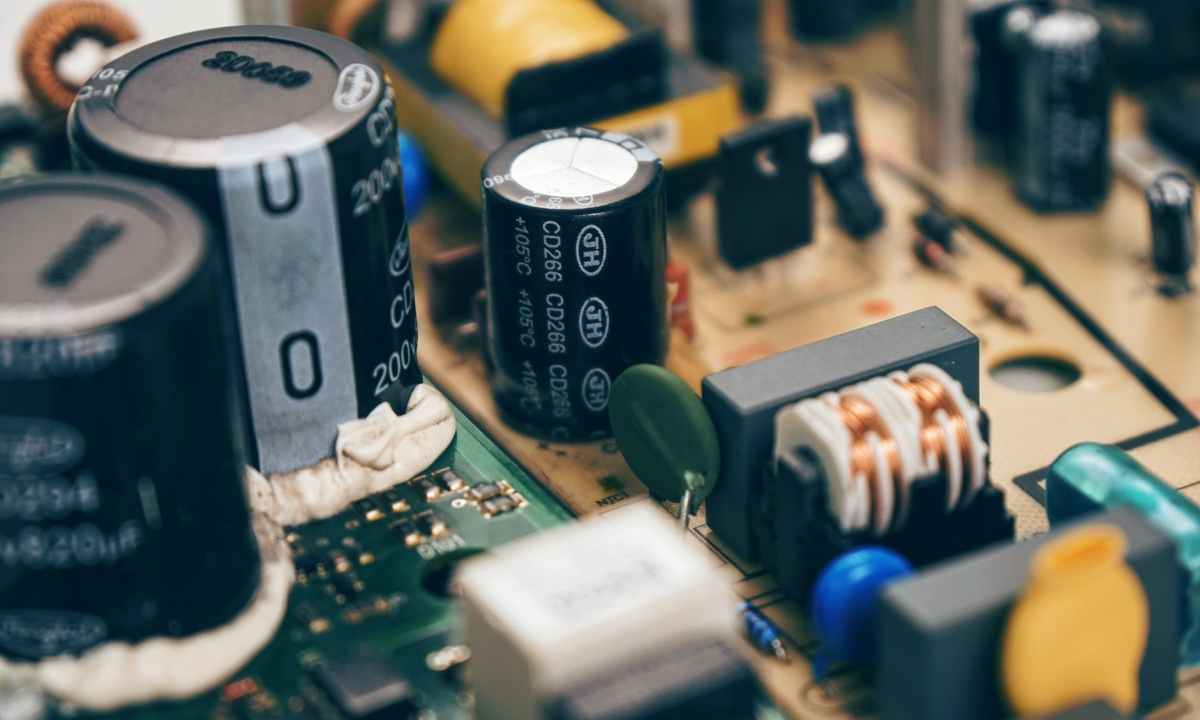

Aging buildings have something in common with aging structures in aviation. There’s always a demand to keep going for as long as possible. There’s always the difficulty of determining the safety margin that is acceptable. There’s always a pressure on maintenance costs.

Believe it or not aircraft structures do fail[2]. There’s a tendency to forget this source of incidents and accidents but they never go away[3]. What happens in industries where safety is a priority is investigation, feedback and learning from incidents and accidents. The aim being to ensure that there’s no repeat of known failures. Rules and regulations change to address known problems.

The vulnerability to moisture and the limited lifespan of RAAC should have been a loud wake-up call. No doubt it was for some well-managed, well-resourced enlightened organisations. Central Government has bulked at the cost of fixing this known building safety problem. A culture of delaying the fixing of difficult problems has won.

In civil aviation there’s a powerful tool called an Airworthiness Directive (AD). It’s not something that an aircraft operator can ignore or put on the back burner. The AD can mandate inspections and changes to an aircraft when an unsafe condition exists.

In the schools cases in the News, the impression is given that Government Ministers have dragged their heels and only acted at the last possible moment. Maybe the construction industry and public estate needs a strong regulator that can issue mandatory directives. Known unsafe conditions should not be left unaddressed or significantly delayed.

[1] https://www.local.gov.uk/topics/housing-and-planning/information-reinforced-autoclaved-aerated-concrete-raac

[2] https://www.faa.gov/lessons_learned/transport_airplane/accidents/N73711

[3] https://www.faa.gov/lessons_learned/transport_airplane/accidents/TC-JAV