This coming week an international tradeshow takes place in London. It’s easier to get to than it’s ever been, at least for me. The wonderful new Elizabeth line[1] goes directly to the ExCeL London.

The organisers describe the event as for the commercial aviation aftermarket. Personally, I don’t like those terms, but I guess it’s a way of grouping together all the activities that happen after an aircraft has been delivered by an airframe manufacturer. That’s maintenance, repair, overhaul and a good deal of other activities. It might be sophisticated test equipment or spanners. It might be hanger facilities or complete aero engine overhauls.

MRO Europe[2] is a major European event. Along with the exhibition there’s a conference highlighting some of the challenges aviation faces. There are a whole lot of uncertainties that are rippling through the industry. Recovery from the impact of the COVID pandemic is happening but it has taken its toll.

The conference subject that caught my eye is that concerning the shortage of qualified people. Civil aviation must compete with every other international technology-based industry. Long gone are the days of the 1960s and 70s when aviation was associated with glamour and a kind of post-war kudos. Now, those with the right abilities, attitude and experience can command excellent reward packages in a wide variety of digital high-tech industries.

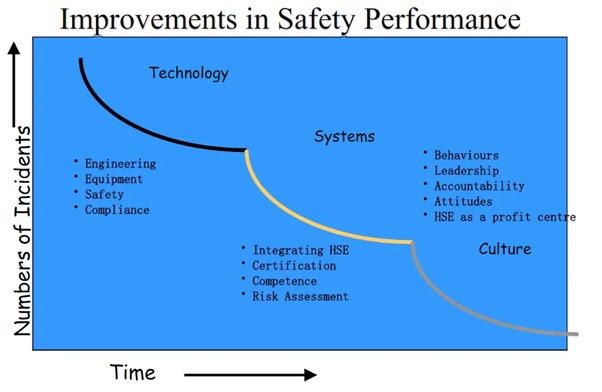

The MRO industry is aging. Offering an attractive pathway to young people is proving to be difficult. It’s a two-sided problem. On the one side the industry is inherently conservative. Afterall it’s in the safety business where reputation for quality matters. On the other side the attitudes, beliefs and expectations of younger people are markedly different from those of their potential mentors and teachers. Bridging this divide isn’t easy.

Apprenticeship schemes do help[3]. However, they are often picking up the people who already know they want a career in aviation.

The challenge is not just recruitment but retention. The aviation industry must make it attractive to retain talent. Working in an aircraft hanger, or on the ramp in the middle of a cold winter isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. Especially when comparing stories with a colleague in a nice warm office of a telecoms or social media company.

Building community, professionalism and a love of aviation is a priority. I’ve seen this done in the US. Next April at MRO Americas at the Georgia World Congress Center in Atlanta a competition[4] takes place. It’s an excellent example of how to create excitement in this field. Check it out.

[1] https://tfl.gov.uk/modes/elizabeth-line/

[2] https://mroeurope.aviationweek.com/en/home.html

[3] https://www.stsaviationgroup.com/sts-aviation-services-launches-newly-formed-apprenticeship-scheme-united-kingdom-1/