It’s a confusing film. I enjoyed it in a strange way. This is one of many times fiction has wrestled with the idea of parallel universes. “Everything Everywhere All at Once” gets crazy[1] and has some absurdly funny moments. Embracing all possibilities, however unlikely is a lot of fun. Childlike fun.

Life’s branches – it’s easy enough to grasp if there are a not many to think about. Lifelong “what ifs” are familiar territory. What if, I’d taken a different path? What if, I’d met this person instead of that person? What if that accident had been more, or less severe? It’s so human to play with imagination and different scenarios. What’s difficult to grasp is the notion that there might be an infinite number of different branches in and infinite numbers of universes.

When large numbers of possibilities arise, it can be the source of anxiety. Me being on the stoic side, I shrug my shoulders and carry on. Don’t get me wrong, thinking about lost opportunities or idiotic mistakes stirs-up more than a few feelings. Living in synchronisation with reality means choosing to focus on changing the things that can be changed and choosing not to bash one’s head against a wall. The key words being to choose.

This is the time of year when future students are looking at future possibilities. Walking past the gates of the local college, a group of school leavers could be seen eyeing up the building. That one first major step at 16 years. Up and down the county, universities are hosting potential students. Trying to answer all their questions. That step, at 18-years is one of the biggest those lucky enough to make, get to make. This town, or city, or that out-of-town campus.

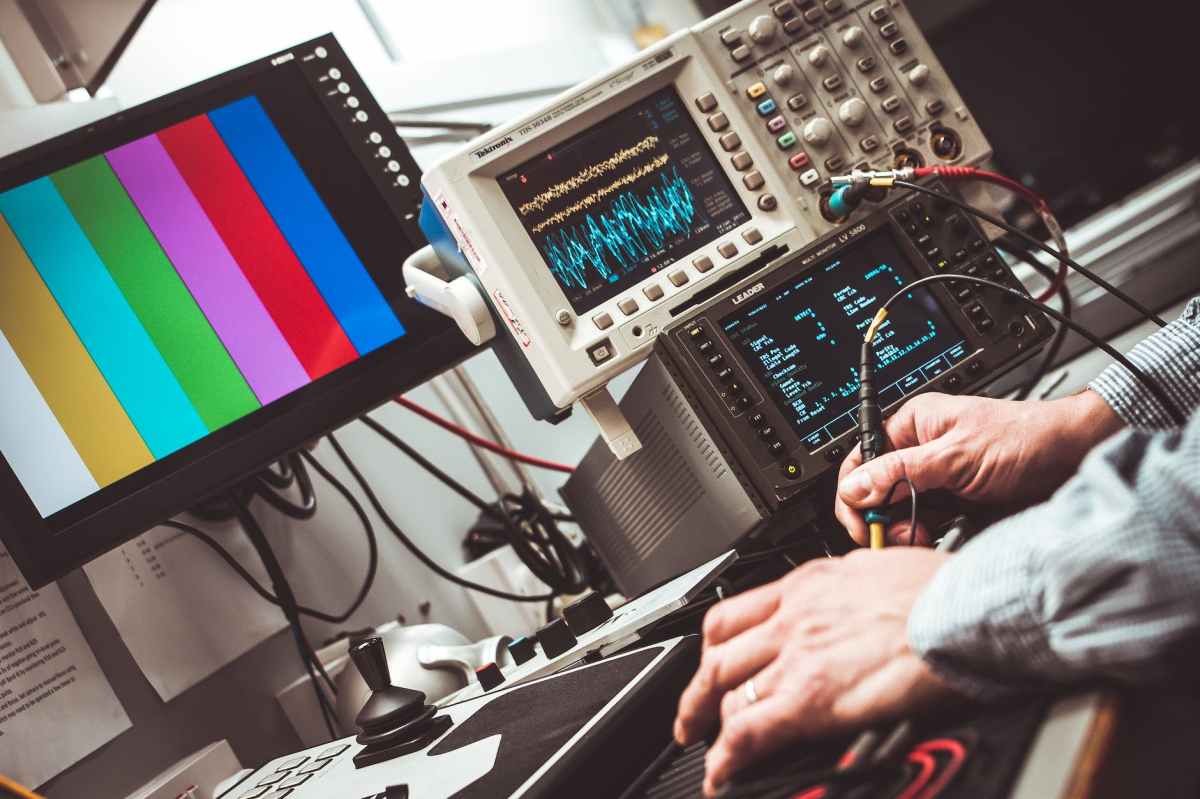

I wonder what I’d be doing now if I’d gone to Bath university or Brunell in Uxbridge? How did I make those choices? Well, there was the factor of sponsorship so there was no way that the chance to study art, politics or philosophy would come up. My search was for a sandwich course to be able to mix study and work. My chosen trade was electrical and electronic design. That fascination with how stuff works continues to this day.

At 18 years, I had little grasp of the fact that university, or polytechnic as it was, was far more than technical study and the usual bundle of exams. The 4-years I had going backwards and forwards between the west country and Coventry was a mammoth transformation.

Although, I had no particular leaning towards aviation there was moments when aircraft and aeronautics came into the mix. On my journeys north to the midlands, I’d often stop at a lay-by at the end of the runway of RAF Kemble and watch the Red Arrow practice[2].

Coventry in the early 1980s was the home of GEC. That being the case there was a telecommunications bias in some of what we were taught. That suited me fine. Let’s face it, in that period we lived in an analogue world with a strong technological push to adopt the early generations of digital systems. Although electro-mechanical telephone exchange production had finished[3] much of the installed equipment in the country was still a mass of relays.

Coventry between 1978 and 1982 was the place to be. It was rough and ready. It was suffering the onslaught of Thatcher’s march to destroy the past and transplant the new. The pace of change left oceans of people behind. Culturally the pressure of that grim social revolution liberated a generation of music and rebellion that we look back on as magic.

As if by magic, and I didn’t plan this, BBC Radio 4 is playing “Ghost Town” by The Specials[4]. Yes, that was a defining soundtrack to influential moments in my life.

[1] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt6710474/

[2] https://the-buccaneer-aviation-group.com/history-of-cotswold-airport/

[3] http://www.telephoneworks.co.uk/history/gec_telecomms.htm