It’s often forgotten that there’s a need to repeat messages. We are not creatures that retain everything we see and hear. There are exceptional people, it’s true, those who cram away facts and have an amazing level of recall. Often that’s my reaction to watching students leading teams on University Challenge[1]. How on earth do they know those obscure facts?

Most of us do not respond well to those who say, “Well, I told them once. I’m not going to tell them again.” That line is probably one of the most misguided utterances a teacher can make. Like it or not, this approach is part of our heritage. Past ages, when deference was expected, listening was mandatory, and misremembering was entirely the listener’s fault.

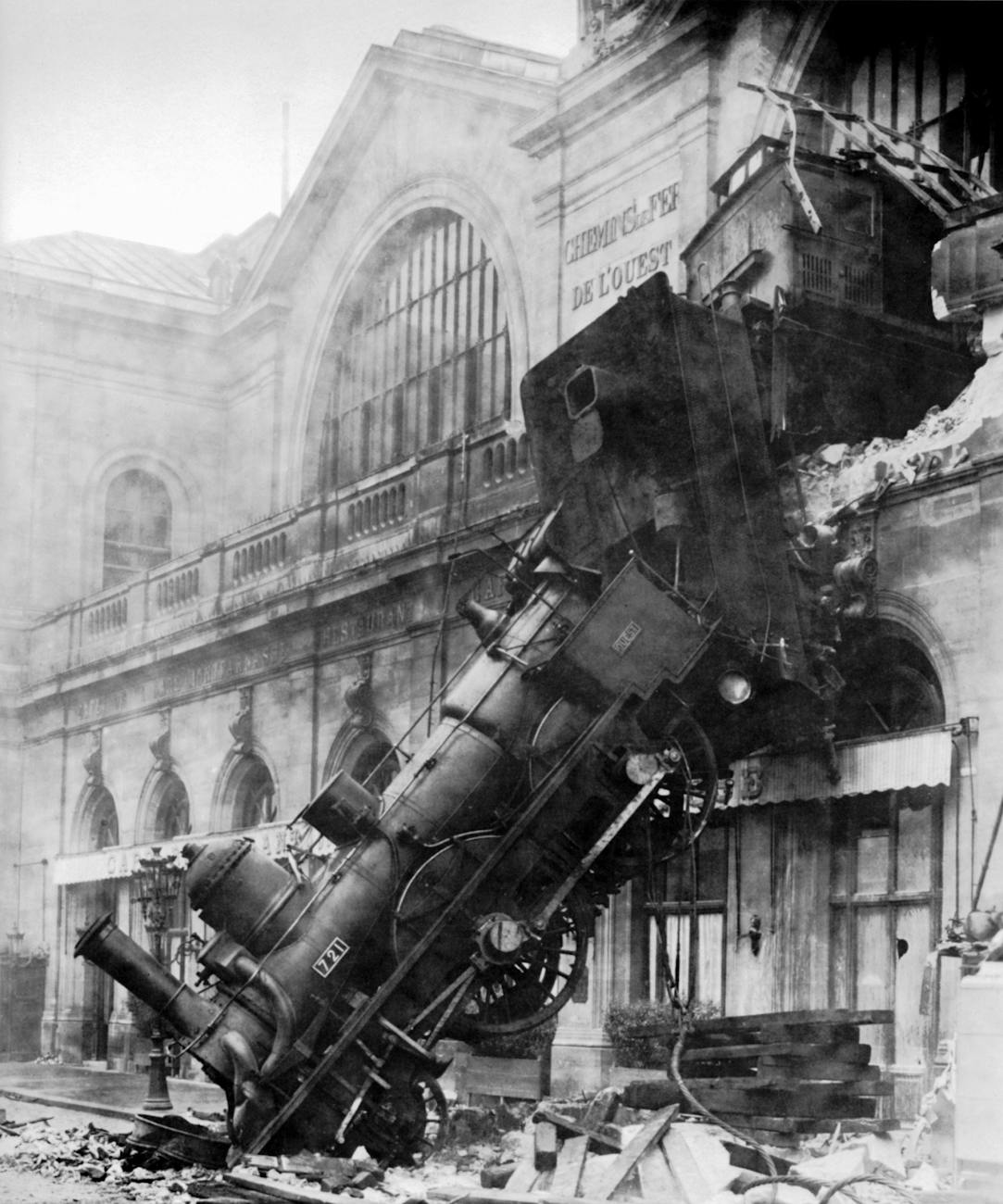

We’ve had a cultural shift. Our complex technological society doesn’t work in a command-and-control way. Too many disasters can be traced to miscommunications and misunderstanding. Now, the obligation exists on those delivering a message to go some way to ensure that it’s received with a degree of comprehension. That’s when repetition has a role to play.

One of the pillars of Safety Management Systems (SMS) is Safety Promotion. It’s the Cinderella of the aviation safety world.

Why do I say that? Experience for one. It’s much easier to get policy made and funding for the “hard” sciences like data acquisition, analysis and decision-making systems. These are often perceived as providing tangible results. Actionable recommendations that satisfy the need to be recognised as doing something. Even if that something is questionable.

Communication is key to averting disasters. It’s no good having pertinent information and failing to do anything with it, other than file it. The need to know is not a narrow one. Confined to a specialist few.

Let’s go back to 2003 and the Space Shuttle Columbia accident[2]. This craft was destroyed in a disaster that claimed the lives of its crew. The resulting investigation report is extremely compressive, if slightly overwhelming, but it has some key points to make.

To quote, “That silence was not merely a failure of safety, but a failure of the entire organization.” [Page 192]. In other words, the hidden concerns and internal machinations of an organisation can smother safety messages and led to failure. Since 2003, it’s sad to say that there are multiple occasions when what has been learned has been ignored. The impact has been devastating.

So, to shape the future let’s remember the Cinderella of the aviation safety. Discovering problems is not enough. It’s vital that practical solutions and good practice gets promoted. That needs to be done forcefully and repetitiously.

NOTE: This is, in part, a reaction to watching this video presentation. https://acsf.aero/an-unforgettable-closing-to-the-2025-acsf-safety-symposium-with-tim-and-sheri-lilley/

[1] https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b006t6l0

[2] https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20030066167/downloads/20030066167.pdf