It’s not an original thought but science, and its advancement, is like a venerable oak tree. Roots spread over a large area, are not seen, but are critical to the health of the whole tree. Branches expand as the tree grows. Branches divide, some branches fade and others gain ever more strength. A tree that lives as long as a civilisation, ever changing.

I put this view forward only to admit that there are flaws with this way of thinking. For a start, in the past, a branch of science may have been pursued in a pure manner. Accumulating ever more knowledge on a specific subject. Now, the branches of science have become far more intertwined. Complexity is a given.

This makes a futurologist job harder. It’s no good to dream along straight lines. To see progressive development as the most likely direction. In the past, there was mileage in projecting forward along a clear line of thinking. Take for example the opening up of the atomic world. Futurologist in the 1950s imagined a world of limitless energy. Inexhaustible sources of electrical power that would be cheep and available to all. For good or ill, the age of plenty didn’t happen. That doesn’t reduce the importance of fundamental discoveries. It cautions us in extrapolating from a simple beginning to a fantastic new world.

What will life in the 22nd Century be like? I can say with certainty that I will not see the year 3000. Well, that is unless the cryogenics of science fiction stories soon becomes reality.

One approach is to look back 75 years. Compare and contrast. Then look forward 75 years. That is factoring in an acceleration in discoveries and the exploitation. And as I’ve alluded above not being shy of growing complexity.

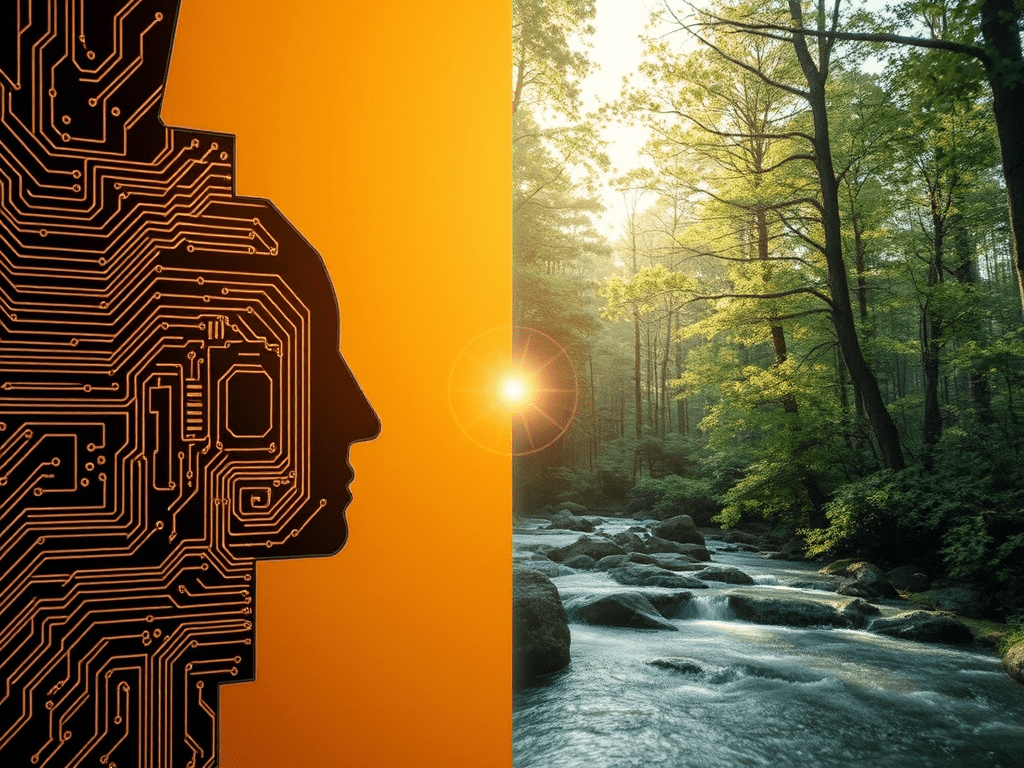

This is again an approach to be taken with a fair degree of caution. Back in the 1950s there was talk of electronic brains, as the computer emerged as a viable and useful machine. What was imagined then is now quite different. That use of the word “brain” isn’t common parlance. Instead, the advent of so-called artificial intelligence is becoming everyday language.

Another set of cautionary factors are trying to guess the branches of the tree that will decay and fall. What seems promising based on current technology only to be bypassed by discovery and innovation. Here I’m thinking that the building of massive power-hungry data farms may be a technological cul-de-sac. Vulnerable and hugely expensive physical infrastructure that’s out of date the minute it’s switched on.

Each of us has a brain that weighs a lot less than a room full of cabinets of conventional electronics. Nature manages vast amounts of data without a power station in tow.

In the year 3000, I maintain we will have a rich and rewarding intellectual life. It will be different in form, although the things that amuse and entertain us may not be so different. The themes of a Greek play are still likely to be echoed in the stories of the next millennia.

Artificial intelligence will be a junk yard term. The whole of the world of data communication and processing will be hidden under layers of obscuration. It’s possible that a form of agent will be overseeing the mechanisms for providing the services we demand. The great challenge for democracies will be how to ensure that agent works for the public good. Not so easy.